The 755 census in the empire of the Chinese Tang Dynasty recorded 52,919,309 persons residing in the realm. In 764, only nine years later, the census stated that 16,900,000 persons lived in China. So what happened in between? I’m so glad you asked, because the story is oddly forgotten to popular memory. How could 36 million people die in less than a decade when the world’s population was still relatively low, and the massive-scale weaponry used today was still unavailable?

Now, a little disclaimer here, one of the main answers might lie with the fact that after the crippling An Lushan Rebellion, the government lacked the infrastructure to go find every single person living within the realm, but even if methodology changed (which the roundness of the second figure might suggest), a lot of people still died.

So, to begin, we’ll do some background. In 712, a guy named Tang Xuanzong (also called Tang Minghuang, meaning “Brilliant Emperor of the Tang”) took the imperial throne in Chang’an (Beijing would not be the capital of China for some time yet).

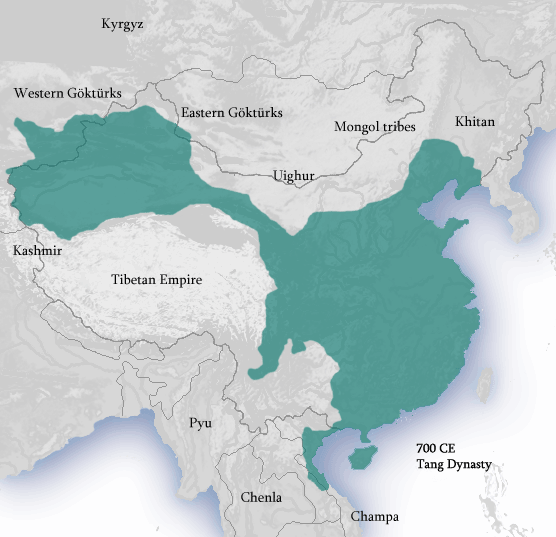

At the time, the Tang Empire was the most powerful China had seen in about five hundred years, since the fall of the Han (technically, so the Han kind of came back, but it wasn’t the same). The Tang had enjoyed considerable success against the Turks, Tibetans, and Balhae (in Korea), and things seemed to be going right for the empire. Xuanzong re-organized the military, and his reforms brought in a number of non-Chinese (for whatever value “Chinese” existed as an ethnicity), even recently subjugated, soldiers. Among these was one An Lushan. His mother was a Göktürk, but his father’s identity is still unknown. One way or another, An Lushan rose through the ranks considerably quickly.

Apparently, he was noticed, for in 743, he was brought before the Emperor himself in Chang’an (this was a really big deal for a foreigner to be invited to the court, as you might assume). A number of perhaps apocryphal anecdotes survive from this time, but the Tang records and histories are surprisingly detailed, so we cannot dismiss them entirely. An Lushan apparently had a thing for the Emperor’s concubine Yang Guifei (formerly his son’s, but in 737, the emperor figured he might as well take her for his own; great dad), because he, on one occasion, bowed to her before the Emperor. When he got called out on it, he said, “Oh, well, we barbarians typically bow to mothers first.” Apparently there’s a number of other instances where he slighted the Emperor and then said, “Oh, well, it’s just a Göktürk thing. My bad.”

Xuanzong apparently bough it, because the sources say that An Lushan continued to rise in his favor despite these episodes, likely due to Yang Guifei’s constant praise of him. In 755, with rising discontent due to the obvious excesses of the Tang court, An Lushan declared a revolt, calling himself the adopted son of Yang Guifei, although contemporary critics alleged an affair between the two of them. An Lushan’s actual military prowess is questionable, however, since early in the rebellion, much of his army was massacred at the Battle of Yongqiu. The sources say that he had 40,000 soldiers, compared to the loyalist army of 2,000. This seems like an exaggeration, but it’s fair to assume that this was a battle An Lushan was supposed to have won, and instead he got slaughtered.

The main thing that sustained the An Lushan rebellion at the beginning was continued court intrigue among the Tang that prevented Xuanzong from assembling any real army to respond to An Lushan’s revolt. An Lushan approached Chang’an with limited resistance, and in the summer of 756, the city, which had a metro population of roughly 2 million, was sacked. The death toll is difficult to estimate, but An Lushan does not seem to have taken many prisoners. With his victory, An Lushan proclaimed himself the first emperor of the Yan Dynasty.

As Xuanzong fled, he seems to have gone through a sort of personal crisis, as he abdicated the throne and made his son the new Emperor Suzong. Around the same time, the Yang family, from whom Yang Guifei hailed, joined the rebellion, which cast considerable doubt upon the motivations and loyalties of Yang Guifei herself, and while the imperial court evacuated Chang’an, the concubine was murdered by angry courtiers who blamed her for the rebellion. The rebellion almost seemed complete at this point, but Tang Suzong responded by hiring thousands of Arab mercenaries and the Khagan of the Uighurs to hold off the Yan advance. Compounded with the increasingly erratic behavior of An Lushan himself, the rebellion suddenly found itself facing serious problems. The rise of famine in the North crippled their supply lines, and, fair or not, An Lushan was blamed. The self-proclaimed emperor had been suffering from a number of ailments, including glaucoma, which left him effectively blind. Ulcers caused him constant pain, and the emperor became prone to caning or even impulsively executing his servants. Out of friends and out of resources, An Lushan was murdered by his son An Qingxu. Qingxu was no more successful than his father, and in 757, the Yan were fought to a stalemate at the Battle of Siuyang – the first time the Tang had been able to meet the Yan in open combat since the fall of Chang’an over a year before.

For the next couple of years, the only general who could make any headway for either side was the Yan’s Shi Shiming, but he and Qingxu seem to have had a difficult relationship in that when Qingxu tried to replace Shi Shiming after his advance slowed down at Fanyang, Shi turned around and killed the emperor. There seems to have been a lot of uncertainty as to whose side Shi Shiming was on in the aftermath of Qingxu’s murder, but fairly soon, it became clear that Shi Shiming was on his own side. He and his 100,000 soldiers rolled across the countryside virtually unopposed, but in 761, Shi Shiming was captured, ambushed, and then strangled when his captors feared they would be pursued, thus ending the An Lushan Rebellion. Pockets of resistance would continue until the autumn of 763, but Suzong was eventually able to re-establish Tang control over most of the country.

Now, this is the story of the “Brilliant Emperor,” who was so brilliant, that he promoted an apparently incompetent military commander, who was fooling around with his favorite wife, whom he had stolen from his son. The Tang dynasty would never truly recover from the An Lushan Rebellion, despite Suzong’s apparent competence, but perhaps the most lasting effect of the rebellion was that those Arab mercenaries I mentioned didn’t go home. Instead they stayed in China, evidently settling among the Hui people in the Northwest, who are, to this day, predominantly Muslim. Ever since, Islam has been a somewhat small, but still vocal, minority in China, and tension between the East and the Muslim minorities in the West has been a continued narrative over the centuries. Like I said, the exact death toll of the war is impossible to determine, but the censuses at least tell us that at the end of the war, the Tang dynasty had less than a third of what they used to have to tax and recruit into the army, which alone would be enough to cripple any empire.

So, the lesson for today, don’t take your sons’ concubines. That’s weird. Don’t do it.