To start our story, we’ll be going pretty far back – all the way to 238 CE in the Korean Peninsula. The Han Dynasty in China had just fallen apart after an admirable 400-year run, and in its place, three rival emperors, each naming himself the rightful successor to the imperial throne, emerged. For the purposes of our story, only one of these is important – Cao Pi, whose son, Cao Rui made an alliance with the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo in 238.

The purpose of this alliance was primarily to re-subjugate the Gongsun Clan, which had grown increasingly powerful in the Northeast over the past few years. The Gongsun campaign went fairly quickly, but thereafter Cao Rui’s kingdom, Cao Wei, saw little reason to remain allied with Goguryeo. With King Dongcheon of Goguryeo’s raid on Wei territory in 242 (apparently he thought his old allies wouldn’t mind), the alliance broke down entirely, and in 244 and 245, the Wei army devastated Goguryeo’s army and countryside. However, Wei never bothered to actually occupy Goguryeo, aside from a few following punitive expeditions, and so they allowed the kingdom to rise again.

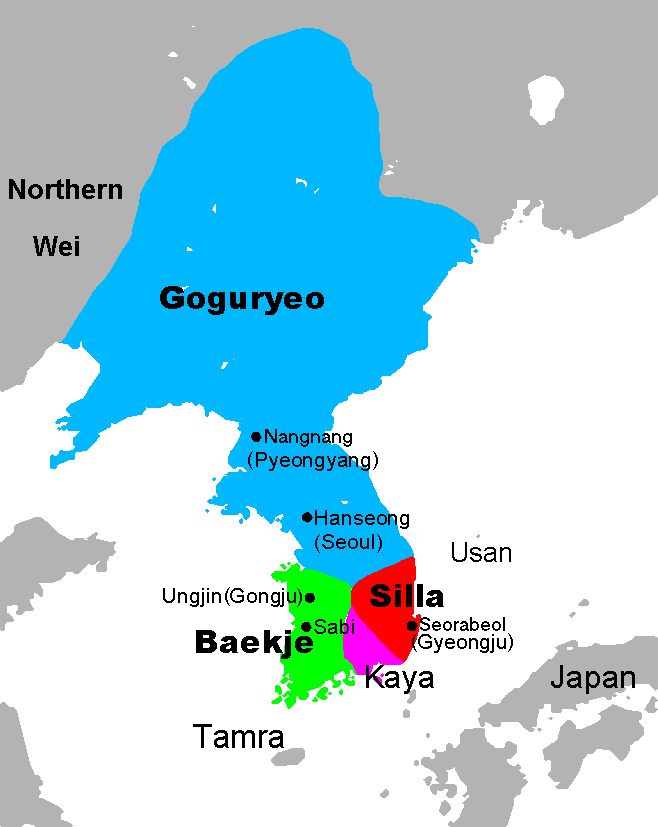

Meanwhile, in the South, old tribal confederacies were beginning to form into hereditary monarchies. The old Mahan Confederacy was consolidated into the Kingdom of Baekje under King Goi, and in the Southeast, a new kingdom called Silla emerged. Between the two southern kingdoms lay the tiny, yet still influential, Kaya (also spelled Paya) Confederacy.

In the mid-4th Century, Baekje began expanding to the North, against her much larger neighbor of Goguryeo. Goguryeo had been weakened by a coup in the year 300, and the following thirty-year reign of the ineffectual Micheon. Micheon’s successor Gogugwon is perhaps more difficult to evaluate, but it was on his watch that the much larger and, until that point, more powerful Goguryeo was defeated by Baekje. Gogugwon was killed in battle in 371, seemingly sealing the decline of Goguryeo. Gogugwon’s successor, Sosurim, however, decided that if Goguryeo were to survive, it would have to modernize. Sosurim set up several laws to decrease the power of individual clans and tribes and to increase national identity in his realm.

In 391, Gwanggeato ascended the throne of Goguryeo, at a time when there was still some mystery as to who the most powerful nation on the Korean Peninsula was. Gwanggeato was only nineteen at the time of his accession, and he was thirty-nine when he died, but during his time on the throne, he forced every single southern country to pay him tribute and to recognize him as their suzerain. Upon his death, the southern kings immediately stopped paying tribute, but the seeds of Korean unification had been planted.

Baekje would decline throughout the 5th Century, and in the early 6th Century, the name “Goguryeo” was changed to the somewhat more manageable “Goryeo.” Over the course of the mid-6th Century, Silla would become the leading power in the South as it annexed the Kaya confederacy and, together with Baekje, they conquered the populous and wealthy Han River Basin. Before Silla and Baekje could advance any father, however, their alliance broke down, and Silla began a series of wars with Baekje. Silla gained the upper hand in these, partly because of their rigidly-organized society. The so-called “bone rank system” was a sort of caste system for Koreans. Clothing, estate size, and how far one may go to find a bride were all dictated by one’s societal class, and Baekje could never match this sort of state control.

The real impetus for Korean unification, however, came with the rise of the Sui Dynasty in China, under the half-Turkic general Yang Jian. Yang Jian fought a small campaign against Goryeo, which the Korean kingdom managed to survive, but the common threat to the West began to concern the Koreans, particularly as Yang Jian’s son, the Emperor Yangdi, began preparing to launch a second, yet larger, offensive into Korea. The Battle of Salsu in 612 was a watershed event in Korean history. Allegedly, over 300,000 Chinese soldiers were slaughtered, crippling the Sui Dynasty. Ordinarily, such a large number would be ignored, but the implosion of the Sui Dynasty that followed soon afterward lends some legitimacy to this claim.

The Sui Dynasty was soon followed by the Tang, who did not lose interest in the Korean Peninsula. After a few failures against Goryeo, the Tang allied themselves with Silla, believing that Silla could become a client state of theirs. Silla conquered Baekje in 660, despite intervention from Goryeo, and in 668, Tang and Silla forces subjugated Goryeo itself. Now, the Tang deployed their “master stroke,” turning on Silla in 670. After a six-year war, Tang and Silla agreed on a border at the Taedong River.

Traditionally, many Korean historians have called this the founding of a unified Korea, but when one actually looks at the map, it’s pretty clear that Silla did not hold all of the peninsula.

The Tang would not hold on to the Peninsula for long, as a revolt from the Khitan people allowed the former territory of Goryeo, along with the Mohe people (ancestors of the modern Manchus) to establish their own kingdom called Balhae in 698. For two centuries, this balance of power persisted, until in 892, with the onset of the Later Three Kingdoms Period.

In the ninth century, people had started to resent the bone rank system (who could have seen that coming?), and before long Silla began falling apart. The kingdoms of Hubaekje (later Baekje) and Hugoguryeo (later Goguryeo) were established, almost as if people thought that repeating history would give them a more favorable result. At first, Hubaekje was the most powerful kingdom, but King Taejo of Hugoguryeo took the upper hand, and by 940, Korea had been reunified, and Taejo’s campaigns against Balhae had given him control over the entire peninsula under the standard of Goryeo.

Historians still disagree as to whether Silla’s “unification” actually counts as a unification of Korea, and, as you might expect, the debate is highly politically charged. Goryeo was a northern kingdom, and most of the historians doing the debating here are from the Republic of Korea – or South Korea. As a result, they would love to portray history in such a way that might lend legitimacy to South Korea, rather than dwelling on a past when the North conquered the South. If we can say that the first nation to unify Korea was a southern kingdom, however, it – after a certain sense – could make it seem like the Republic of Korea has a “right” to North Korea. Of course, the honesty of the discourse on the history of Korean unification was largely influenced by the heavy censure of free speech that South Korea endured for most of the 20th Century. In recent years, scholars have had a more honest debate that has begun to consider Goryeo’s conquest in the 10th Century the first time Korea – and all of Korea – was truly united.