So, the more that I think about this, the more I begin to realize how daunting a project this is, because Shivaji’s life is basically an action movie. The pseudo-founder of what would later be known as the Maratha Confederacy, Shivaji remains one of the most famous and heralded figures of Indian history. Part of the difficulty is separating the myth and cult of personality that has now developed around Shivaji from the historical man. Part of the distortion of Shivaji’s image is due to the Hindu Nationalist movement (hence, why I decided to talk about the Hindu Nationalists on Sunday), as he was the first Hindu ruler of any importance on the Indian subcontinent since the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire over a century before. Shivaji’s conquests protected a Hindu faith that had come under increasing amounts of persecution under the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, and he used the “moral high ground” as a major weapon in his war against the Mughals.

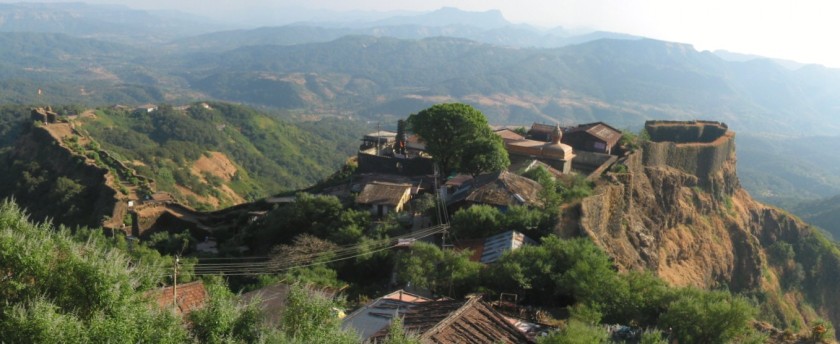

Shivaji was born in Pune in either 1627 or 1630. Not real important which. It is important to note, that Pune District remains one of the strongest bastions of the Hindu Nationalist movement to this day. Nathuram Godse, the man who murdered Mahatma Gandhi, was, fun fact, also from Pune. So when Shivaji was pretty young, in 1645, he apparently bribed a local official from the Bijapuri Sultanate (a minor state in the Deccan, in central India) to hand over a fort to him. Now, you might not think this is a big deal, but explain to me how a minor 17th Century Indian monarch is supposed to conquer this…

Because that’s what Shivaji got. Before long, another fort had pledged allegiance to him, and he had bribed a second commander out of his fort. The Bijapuri Sultanate was not large enough to ignore something like this for long, because this was not the first time that the Maratha had been problematic.

It’s important to understand that around this time, Hindu philosophy was really taking off. Unlike most religions, there’s no single figure that really founds it. It is, rather, an accumulated set of beliefs and traditions that have been practiced in India for thousands of years beyond memory, and although there remained (and still do remain) substantial differences among Hindus, there was a certain common identity, and this gave people something to rally around. At this time, Indian, and particularly Northern Indian, politics had been almost entirely dominated by Muslims for about 600 years, but the Muslims only made up an estimated 8% of the population at the time (it’s a little more now). However, the “Hindus” never really thought of it as a religious war. They viewed it as mostly an ethnic conflict with the invading Turks, but because they wrote so little about what they thought about the whole thing (or at least, almost none of it survives; a notable exception here is the Ardhakathanak by Banarsidas; it’s a pretty easy read and worth reading), we have little means to understand how the Muslims were understood.

What Shivaji brought to this was a military aspect. He never phrased it in terms of a Hindu holy war but more as a Hindu/Maratha war of liberation. He was strongly against forced conversion of Muslims, and he vehemently opposed slavery (although the Hindu caste system doesn’t seem so different from slavery to me).

So, like I was saying before I so rudely interrupted myself, the Bijapuri sultan sent around 30,000, maybe 40,000 guys against Shivaji under the Afghan general Afzal Khan. Shivaji had managed to scrape together around 13,000 by way of comparison, and he had no muskets, compared to Afzal Khan’s 1500. The pair of them met at Pratapgad, and since Shivaji held this fortified position…

Afzal Khan decided he would negotiate with him. What followed was a classic “Han shot first” argument. Some claim that Afzal struck first, while others claim that Shivaji (who, one way or another, definitely brought a dagger to a no-weapons parley, which is more than a little shady) attacked Afzal. One way or another, Shivaji lived (if he hadn’t, this would be a very anti-climactic story), and he and his army routed the now leaderless Bijapuris. By 1660, the Bijapuris had forged an alliance with the Mughals against Shivaji. One of the issues with subduing the Maratha, however, was the terrain. You saw the two forts that I showed above. Dotting the entire rocky, hilly landscape of Maharastra are forts just like or similar to these, and since Shivaji held them with full garrisons of men, he was a nightmare to subdue. It didn’t matter how many people the Mughals sent, manpower was not what was needed. What was needed was better artillery than existed on the Indian subcontinent, or anywhere, for that matter.

Shivaji would never be powerful enough to challenge the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb directly, and after eluding him for years, Shivaji was captured in 1666 and taken to Agra. The details of this part are a little shaky, because the guy either seduced the Emperor’s wife with nothing but the hungry eyes (I’m guessing not), or he just disguised himself and found his way out of Agra. Shivaji’s army had taken a tough hit from clashing directly with the Mughals, but the notion of independence had taken root in the hill country of Maharastra (that’s where the Maratha live and where they speak Marathi).

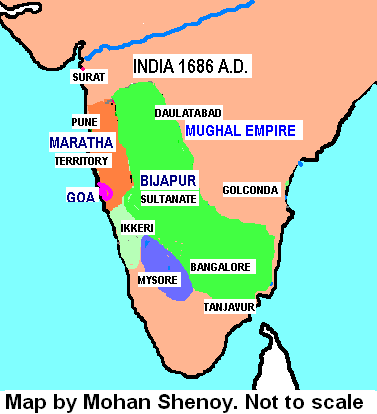

As he got his army back on its feet, Shivaji made a few raids against the British in Bombay (which at the time was rather small, compared to the 20 million person metro population it has today), but for the most part he was pretty quiet. Suddenly, in 1674, when most of the Indian Subcontinent seems to have believed that Shivaji was out of the picture, Shivaji scored a large victory at the Battle of Nesari against the Bijapuris after the Mughals had withdrawn, and Bijapuri power was effectively broken in Maharastra. Worsening relations between Bijapur and Aurangzeb would eventually result in the latter conquering the Bijapuri Sultanate in 1686.

With his lands secured, Shivaji was crowned Chhatrapati of the Maratha Realm later in 1674, and over the next century, the Maratha would become the most powerful empire on the Indian Subcontinent, only being subdued by the surge of British military presence in the early 19th Century. For the last several years of his life, Shivaji fought to secure a stable inheritance for his sons, and that would mean not provoking the Mughal Empire, so instead of attacking the Mughals, he moved south, acquiring additional lands there and surrounding the lucrative Portuguese trading port of Goa, giving him an essential trading partner. Unlike many great military men, Shivaji ensured that his sons would be able to do what he never was – directly challenge the Mughal Empire rather than simply defy it, as he had. This (kind of grainy) map shows the extent of his realm at the end of his life:

So when you look at the size of what Shivaji created, you probably think “Oooooh… what big empire…” but the importance of Shivaji lies not with what his end accomplishments were. Of all these countries you see on the map (and others existed elsewhere) Shivaji was the only Hindu ruler, despite the fact that around 90% of India was Hindu at this time, and, as I mentioned, that gives him considerable cultural significance to this day. Not to mention, he’s notorious for all kinds of badassery that I didn’t really have time to go into here (I mean, ripping a general open with a knife and escaping prison is cool and all, but catching arrows mid-flight is way cooler). He’s the kind of guy who spends almost three decades (1645-1674) of his life either holed up in forts or on the run in the Maharastra countryside, eluding powerful emperors and sultans the whole time. His life was an action movie, and honestly, Hollywood should pick it up (although Bollywood’s already done a few decent jobs on it).