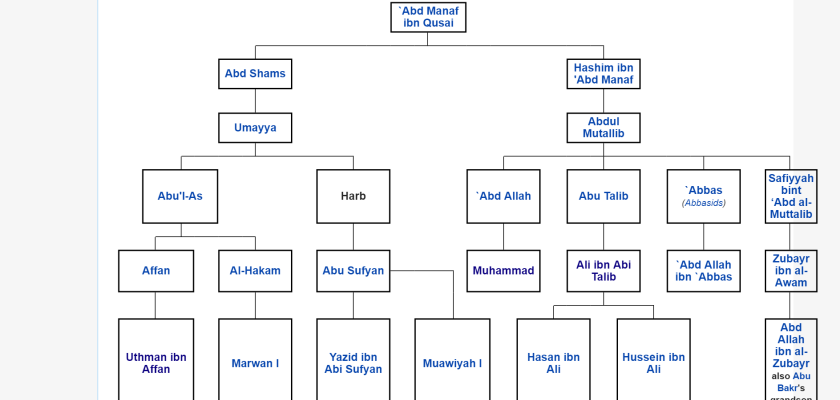

So, the more that I thought about this post, the more I kept on thinking it would be a crash-course in Middle Eastern history, and honestly, in my ~1500 word cap for this post, I simply could not do it justice. As a result, I decided to BRIEFLY describe the succession of Caliphates and explain how they allowed Shi’a to survive. Mind you, there’s been a lot of other people who have claimed to be Caliphs. Later Ottoman Sultans began identifying as Caliphs, the Ahmadiyya Muslim movement in northern India has a Caliph – even ISIS has a Caliph. It really doesn’t take much to call yourself something, but only a handful of people have had the capability to realize the actual power of a Caliph.

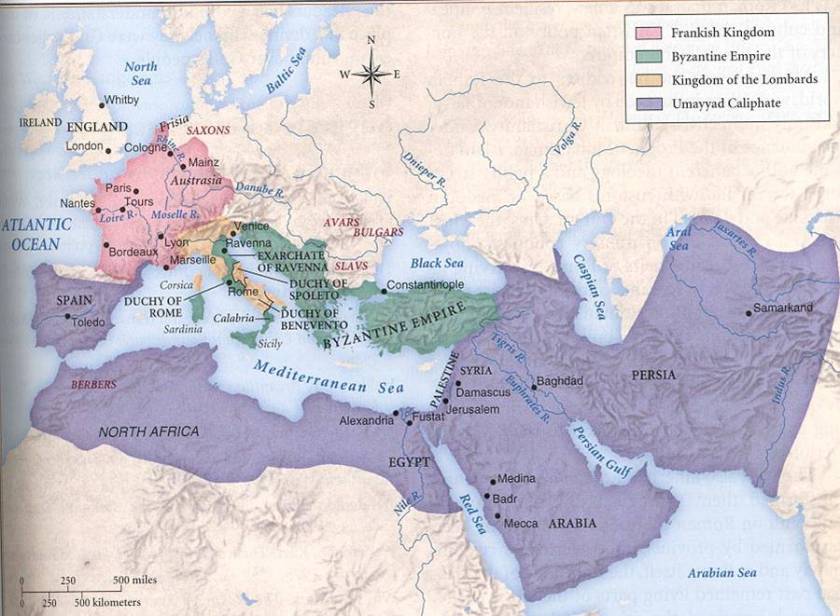

So to start today’s story, we’re going to fast forward to the year 750, which is, I admit, skipping a lot. The Byzantines had more or less given up on the whole idea of maintaining their African empire, as the local Berber and Vandal populations had risen up against them while the Umayyad armies swept across the Maghreb. Under the newly-converted Berber Tariq ibn Ziyad (whose story I’ll tell you someday), the Muslim armies conquered essentially all of Spain, aside from the mountains in the north, where the Basques held out. Meanwhile, the Byzantines had been too busy dealing with the Slavs and Avars in the North and the Lombards in Italy to wage a prohibitively expensive war against the Umayyads.

The Umayyad popularity was largely based on their battlefield success. In fifty years, they had conquered Visigothic Spain, Sindh, in what is now Southern Pakistan, the Caucasus Mountains, and all of the northern coast of Africa. A series of defeats in the mid-8th Century, however, left the Umayyads with very few friends. The first of these came in 718, at the Siege of Constantinople, in which an army of as many as 120,000 Arabs (likely exaggerated but technically possible at the time). The Byzantine Emperor Leo the Isaurian’s signature victory had a number of consequences within his own empire, but in the Caliphate, it set off a chain reaction of losses. In 725, in India, against the Kingdom of Avanti, the Muslim armies suffered what appears to have been a major defeat. Very little information still exists about this, but the momentum of Muslim conquest in India clearly slowed after this. Meanwhile, in the West, what was at least at the time considered a major defeat at the hands of the Franks in Battle of Tours resulted in the abrupt halt of Muslim advances into Europe (I know some people like to downplay Tours, but I’ve never heard a good explanation as to why a follow-up expedition was never even planned).

The lack of historical material about the latter two battles makes their importance somewhat difficult to determine, but what happened soon afterward, with the overthrow of the Umayyad clan, would imply that these were hardly inconsequential to the people of the time period. The revolt of the Abbasid clan in 750 saw everyone save the Arab tribal establishment turn on the unpopular Caliphs. Even the Shias sided with the mainline Abbasids. The Umayyads would re-emerge six years later in modern Spain and Portugal and would set up their own “Caliphate” there, but they would never expand their influence much beyond the Iberian Peninsula.

Now, what does all this have to do with the Shi’a, you might ask? I’m glad you did, because that makes a great segue into my next point… Multiple different Islamic states is what preserved the existence of the Shi’a faith. For the first 150~ years of Islam’s existence, the entire faith was under a single political head. With the Umayyad revolt in Spain, and sixty years later, the Tahirids’ revolt in Persia would make the break-up of the Islamic Empire permanent. With this development, the descendants of Ali could flee to more tolerant nations to escape persecution.

In 909, the first Shi’ite state was established in North Africa. Over the remainder of the 10th Century, they would come to control Egypt and would establish the city of Cairo. Under the Caliph Mansur, the Shias would come to control Jerusalem. Mansur’s an interesting guy in a lot of ways, and his disappearance in 1021 is almost a fitting end to such a bizarre life. All that was found of him was his donkey and bloodstained garments.

Mansur changed his policy on religious minorities several times, even saying a couple of things that almost sound like he thought all religions were basically the same (this is not orthodox Islamic teaching). He was known to impulsively condemn men to death, and he and his men destroyed the famed Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem This led to his moniker “the Mad Caliph” in the West, but in Isma’ili Shi’a, he is considered a sage teacher.

The Crusades, which broke out less than a century after the death of Mansur, would weaken both the Fatimids and the Abassids so greatly that both of them would suffer on as puppet governments for another century and a half, until the Mongol invasions acted as an impetus for their final overthrow. The fragmentation of the Islamic Empire allowed for the survival of fringe groups like Shi’a, which, in the top-down regime of the Caliphs, would not have been able to survive.

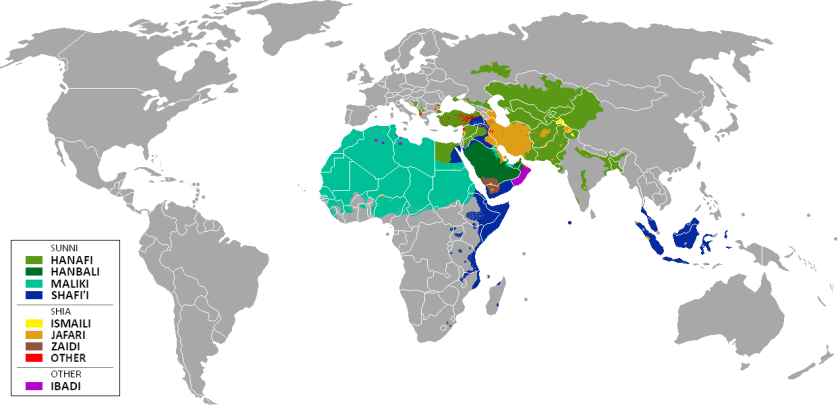

Today, four majority-Shi’a countries exist – Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Bahrain, with significant minorities existing in Pakistan, India, Lebanon, and Syria.

Now, about 1300 years removed from the Shi’a-Sunni split, more splits have occurred within the sects themselves, although within the Sunnis, most all Hanafis would call the Maliki Muslims, the Shafi’i would call the Hanbali Muslims, etc. The only intra-sect split that has become a large, faith-determining issue is the Isma’ili-Jafari split in Shi’a. For the most part, however, Shias and Sunnis do not consider one another to be true followers of the prophet.

So, hopefully this somewhat meandering post covers the bases that my first two posts did not. If you have additional questions, feel free to comment, and I’ll do what I can to answer. Some questions might be better posed to an actual Muslim, however. 🙂

Thanks for reading,

Paul