The fall of the Roman Empire was by no means a pretty thing, and by the mid 6th Century, less than a century after Odovakar sent the last Emperor into exile, the Italian Peninsula, once the heart of the Empire, was completely war-torn. Odovakar had been murdered in 493 by the Ostrogothic king Theodoric, but the Byzantine Empire, the residual eastern half of the Roman Empire that was not dissolved with Odovakar’s dismissal of the Emperor, was not about to let the most densely populated region in Europe go so easily. Repeated campaigns by the Byzantines ravaged the countryside even worse, but internal political machinations within the Byzantine Empire did not allow any permanent gains to be made.

It is upon this background that our story begins, when the Ostrogoths were permanently conquered by the rebounding Byzantine Empire, which appeared poised to re-take all of the former Roman Empire and more. Mostly ignored at the time were the events happening in the Danube River valley.

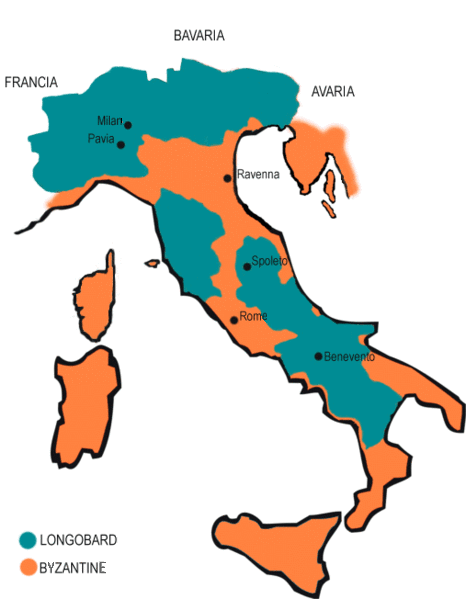

So, One thing you’ll notice is that on the northern border of the Byzantine (here called Roman, because that’s basically what it was) are a few bigger kingdoms, namely the Lombards and Gepids. You’ll see Lombard spelled a bunch of different ways if you research this for yourself, so don’t worry about all that, but the important part to remember here is that the Lombards are in an extremely unpleasant area of the world. It’s cold, but it really doesn’t rain as much as you think it would, and for the farming techniques available at the time, most of it was unarable (unfarmable). As a result, the Lombards were really looking for a place that was not where they were, which led them to fight with their neighbors, the Gepids, constantly.

In 552, the Lombards scored a big win on the Gepids. Most of our history on this stuff comes from Paul the Deacon, who wrote down largely what he was told by Lombards several decades after it happened, but it seems like the Lombard prince Alboin, killed the son of the Gepid king in what was a complete rout. External sources do confirm this, because the Byzantine Emperor Justinian intervened on the behalf of the Gepids, hoping to keep the Gepids and Lombards at each others’ throats so that they wouldn’t turn to the logical next target – the fabulously wealthy Byzantines.

Justinian’s plan seems to have worked at first. Somewhere probably after 560, Alboin succeeded his father to the crown of the Lombards and waged a new war against the Gepids. In 565, the Byzantines intervened once more, although they were by this point much weaker than they had been and were ruled by a new Emperor, Justin II. Either way, the Gepids and Byzantines combined were more than enough to wipe out the Lombards. Alboin, seeing no other option, formed an alliance with Bayan I, Khagan of the Avars, but it came at a price. Bayan demanded that the Gepids’ lands belong to him at the conclusion of the war, plus half the war booty, much of the Lombards’ cattle, and a tenth of the Lombards’ lands. By 568, the Gepid kingdom had been annihilated and subjugated by the Avar horde, and Alboin had slain the Gepid king, taking his daughter, Rosamund, as his new wife.

It didn’t take long for Alboin to realize that he had made a deal with the devil, and Bayan’s posturing made it clear that before long, he would turn on his old ally and take the Lombards’ lands. Alboin determined that he and his people, as they had a century before, would have to migrate south, this time into Italy. Somewhere between 150,000 and 300,000 Lombards around a third of whom would have been fighting fit warriors, made the trek from their homelands in Pannonia to the Italian Peninsula. On Easter Sunday of 568, the Lombards departed, and they don’t show back up on the historical record for a year.

To this day, it is unclear as to whether the Byzantines even knew the Lombards were coming. They were certainly unprepared, but then again, not many countries could be compared for 50-100,000 soldiers invading with an entire nation in tow. No Germanic tribe had done this for almost a century, and the Lombards would be one of the last. Paul the Deacon says that Alboin entered Italy “without any hindrance,” which would suggest that the Byzantines were entirely unaware of the impending crisis, and they were never able to put together a coherent response.

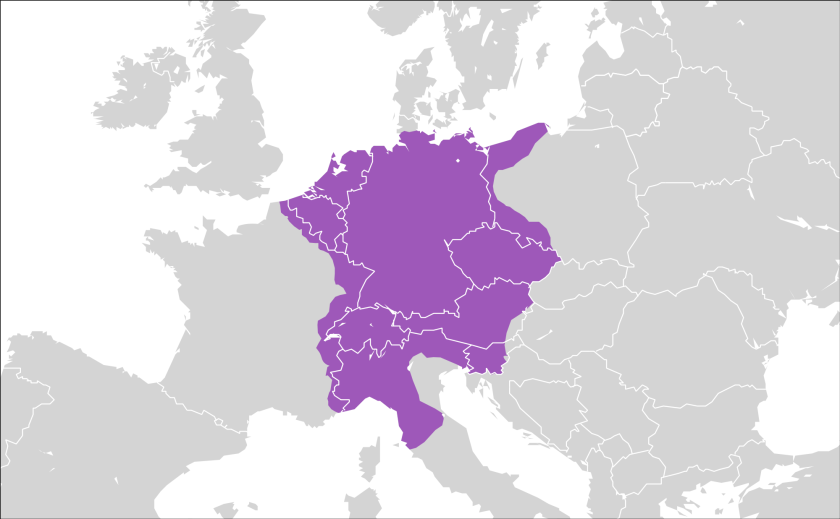

One of the major issues with Alboin’s invasion was that Alboin was an Arian Christian – one who believed that Jesus was not God but rather a special creation of God, neither god nor man, designed to atone for the sins of the world. Arianism had been condemned at the 325 Council of Nicaea (in which Saint Nicholas punched Arius in the face, true story; that’s the same Saint Nicholas who is now your beloved Santa Claus), but the Arians had been much more aggressive missionaries than the orthodox Nicaean Christians had been. Because of this, most of the invading Germanic tribes had, at least at first, converted to Arianism. Through a complicated series of events that I have nowhere near enough time for, Arianism had more or less disappeared, particularly after the fall of the Ostrogothic Kingdom in 553. Now, fifteen years later, another major Arian power was making its presence known.

The Byzantines viewed their struggle against the Lombards as a Holy War, and the influx of heretics into Italy would serve as a catalyst for Pope Gregory the Great (590-604) to lead a sort of evangelistic revival in the Church that would lead to the establishment of the institution we now call the Catholic Church.

Literally the first evidence of anybody resisting the Lombards is at Pavia…

Right there. The Lombards had marched clear across Northern Italy and nobody had said a thing. The issue that the Lombards ran into was that they weren’t used to siege warfare of any sort, and so when a walled city finally refused to surrender out of sheer terror, the Lombards just had to sit outside and wait. This was not something they were good at, and so while Alboin sat there with the main army, his men scattered all around, raiding Burgundy to the Northwest and moving farther south and taking more land.

Alboin also apparently became an alcoholic at this time (although it’s possible that he had been for a while, the unfamiliar Byzantine liquor might have been too strong for him), and an initially ambitious and warlike king became apathetic and lazy. Pavia fell in the spring of 572, after over two years of siege, and Alboin declared a new kingdom of the Lombards, allegedly forging for himself an Iron Crown (more on that later), but the title was, by this point, meaningless. His men had already fought and lost to the Burgundians without his presence or permission. They had conquered much of Southern Italy without his blessing as well. Alboin was a figurehead, if even that.

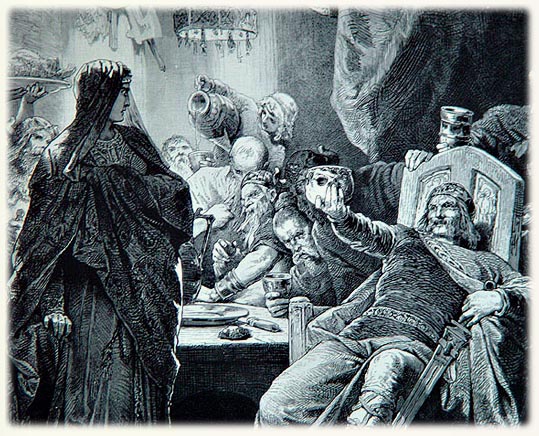

Things came to a head in June of 572, as Alboin’s wife, Rosamund, plotted to murder him. Mind you, we mentioned that Alboin had killed her father fourteen years before, and she probably didn’t just forget about that. Now, a lot of people diverge on the story of Alboin’s murder. Gregory of Tours, a generally solid source but not one who specialized in the Lombards, says that Rosamund had simply bode her time until the opportune moment, whereupon she decided to poison the Lombard king.

Paul the Deacon tells the story differently. He says that Alboin had gotten drunk, as usual, and had been using Rosamund’s father’s skull as a drinking vessel. This might sound like a fantastic tale, but this has been done a lot through history, even as late as the 13th Century among the Bulgars. The Bulgars and Avars seem to have been pretty big fans of the whole skull-drinking thing, and it’s not unlikely that Alboin, seeing the ferocity and speed with which the Avars subdued their enemies, became something of an admirer of the practice. One way or another, he began to taunt his wife and even forced her to drink from her own father’s skull, which rekindled Rosamund’s desire to see Alboin dead.

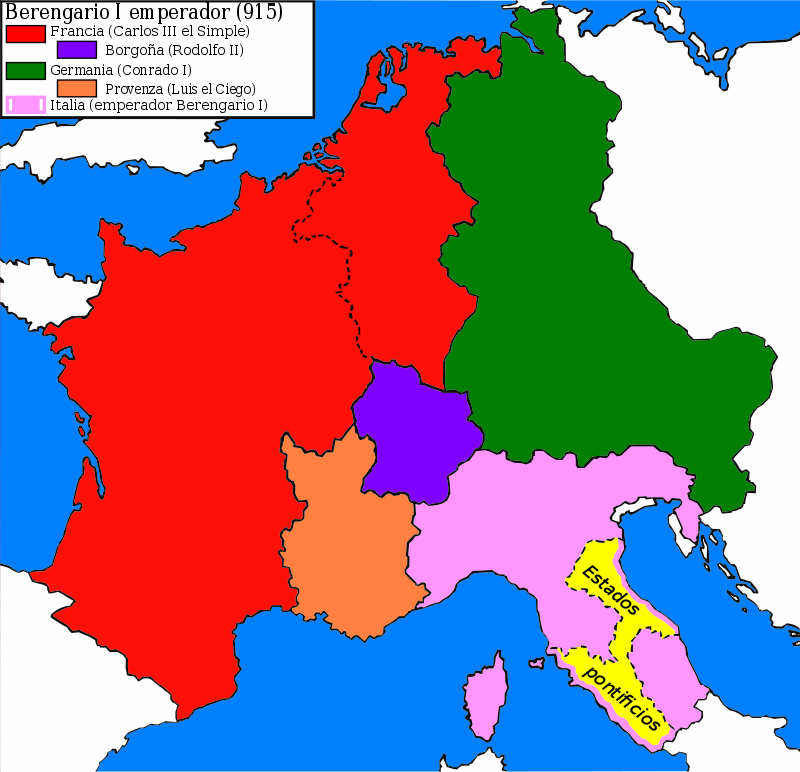

With no real succession plan in place, the assassination of Alboin led to a downward spiral among the Lombards that led to a ten-year period known as the Rule of the Dukes. It would not be until 584, when a foolish invasion of Burgundy would result in a Frankish alliance against the Lombards, that the Lombards would, only out necessity, reunite under a single king.

“King of the Lombards” would never be a powerful title, as the Lombard dukes preferred to maintain their own rights in their own principalities, but the title became symbolically important, as the myth of the Iron Crown grew. Later, when declaring their own position as “King of Italy,” the kings of the Germans would take an iron crown they claimed had been forged by Alboin himself, giving a certain ancient rite to their position. Of course, few German kings were ever able to exercise practical control in Italy, but the myth was created by Alboin, who permanently broke Byzantine hegemony in the Italian Peninsula.